Datenschutz-ErklûÊrung: Ich sammele KEINE Daten und verwende keine Cookies

(Ausfû¥hrliche Datenschutzerklaerung).

Die Hinweise auf meiner Internet-Seite kûÑnnen k e i n e ûÊrztliche Beratung ersetzen.

Es kann keine Beratung per email erfolgen.

Bitte wenden Sie sich an Therapeuten Ihres Vertrauens und / oder a n das

Ohr- und HûÑrinstitut bzw. das Gleichgewichtsinstitut Hesse(n)

Meniere's Disease:

Patient's Guidance with a clear diagnosis, but vertigo provoking perspective.

Translation of the german original:

Schaaf, H., Holtmann, H. (2005) "Patientenfû¥hrung bei M. MeniÕre"

Klare Diagnose, meist schwindelerregende Perspektiven. HNO.

Corresponding adress:

Dr. med. Helmut Schaaf ,

Email: DrHSchaaf@t-online.de ZustûÊndige LandesûÊrztekammer Hessen (BRD)

Please note: It not possible to counsel via internet and email (especially because of my rare english knowledge)

Summary:

Meniere`s disease is characterised by recurrent attacks of vertigo, sensory hearing loss and tinnitus. Meniere-attacks can lead to additional dizziness components.

While diagnosis in recurrent spells is easily secured, leading the patients is as difficult as the mostly unclear development of this - mostly - progredient disease. Fundament of this frequently changing disease is a reliable patient-physician relation, which should be based on a knowledge of all facts of the diseases which do not only include ENT-science but also broad medical counseling.

Key words: Meniere`s disease - psychogenic dizziness - counselling

Meniere's disease is defined as:

"an aetiologically unclear illness, affecting mainly (in 70% of cases) one side of the cochleovestibular organ with the following characteristic symptoms: severe attacks of Vertigo (lasting between minutes and hours), beginning with fluctuating hearing loss, Tinnitus (mostly occurring in low frequences) and a feeling of pressure in the affected ear."

During the acute attack patients - often not knowing what is happening to them - also experience deep anxiety and fear of death, so that the first vertigo attack can be misjudged as a heart attack.

In addition, the differentiation between a meniere attack and the first occurrence of vestibular disorder can be difficult. After the recurrence of the attack, the ear,

nose and throat medical specialist can usually make a clear diagnosis, when also taking into consideration the medical history and the neurootological findings.

Guidelinens along ADANO

along staging according to Jahnke (1994)

Stage 1: Fluctuating hearing loss; this may recover to a normacoustic level after the Meniere vertigo attack.

Stage 2: Vertigo attacks and fluctuating hearing loss, that may improve spontaneously, but not to a normacoustic level.

Stage 3: Severe hearing loss without fluctuation and persistent vertigo attacks.

Stage 4: The inner ear has lost its function.

Subjectivity of the Patient

Through the suddenness and severity of the vertigo attacks patients lose confidence in the stability - previously taken by them for granted - of their vestibular system. Not knowing what is happening to them during the first attack, they often feel helpless and deeply threatened. For patients diagnosed with Meniere`s disease there is a breakdown in their sense of security, which now proves to be vulnerable and threatened by the unpredictability of recurring attacks of vertigo.

In 1861 Prosper Meniere himself vividly described the almost constant problems of a patient:

"Without identifiable cause, a strong young man is suddenly struck down by symptoms of dizziness and nausea; inexpressible fear diminishes his strength; his face turns pale, becomes bathed in sweat and shows signs of an approaching loss of consciousness.

At first the patient feels unsteady and dazed, then he falls to the ground and is unable to get up again.

Lying on his back, he sees the room spinning around him, and the slightest perceived movement increases his sensation of dizziness and nausea. We can observe his pale face, signs of a possible fainting fit, his body bathed in cold sweat and altogether everything indicates a state of deep anxiety."

In 1530 Martin Luther believed his state of illness, at that time not yet known as"Meniere-condition", to be the work of Satan:

"I thought it was the Devil himself, doing everything within his power to make me suffer on this Earth"..."nobody believes how much these fits of imbalance and the roaring and ringing in my ears torment me. I hardly dare to read for an hour, or to concentrate on any matter, because the loud ringing returns with force and I fall to the ground." (4)

A patient reported: "When I had my attacks, it was as if I was awakening from a nightmare, the whole room was spinning, I was violently sick, and most of all I would have liked to have jumped out of one of the many windows circling around me, if I had only been able to reach one of the windows a few metres from my bed, or to choose the right window. I have often enough just wanted to become unconscious."

Reactive psychogenic dizziness

Meniere diseases goes along with vertigo and dizziness; but not every dizziness and vertigo is due to a labyrinthine event.

Undoubtedly and often Meniere's vertigo attacks themselves had consequences for the psychogenic equilibrium of patients. Reactive psychogenic dizziness increased with duration of the disease, and the number of Meniere's attacks.

(more in: Schaaf H, Holtmann, H., Hesse, G, Rienhoff. N. Kolbe et al (2000):

Reactive psychogenic dizziness in Meniere's disease.

In: Sterkers, O; Ferrary, E.; Daumann, R.; Sauvage, J.P.; Tran Ba Huy, R: (eds):

Meniere's disease 1999 - update. Proceedings of the 4th international Symposium of Meniere's disease

Paris, France, April 11-14, 1999.

Kugler Publikcations, The Hague. pp. 505 - 511)

Differentiation between psychogenic dizziness and labyrinthine vertigo:

Because any form of dizziness can be misunderstood as an Meniere attack as duration of illness increases, it is important to differentiate between psychogenic dizziness and labyrinthine vertigo as well as other forms of organically induced dizziness.

In absence of ataxia or impairment of brain-nerves permanent dizziness is most likely psychogenic, especially the more complex the reported dizziness is experienced and expressed, even though the patient may experience it as a vertigo-attack. The only condition being, that even with nystagmus glasses, there is no evidence of nystagmus.

But it is quite important to know that the absence of an organic component alone does not prove psychological dizziness. Therefore it is necessary to outline a psychogenic model of possible circumstances and conditions which make the event understandable.

One simple technique all patients can learn easily is to look for fixed points in the environment when the actual vertigo attack starts. That way the patient can find out if the world is starting to move around him - as it would do in case of labyrinthine vertigo.

If he can fix whatever he is looking at with his eyes without this sensation, the attack is probably psychogenic.

Another method is getting up and stamping or trying to walk.

If this leads to a more steady and stable feeling - and not to falling down - psychogenic dizziness is likely.

59 % of our patients suffered mainly from reactive psychogenic dizziness.

It occurred even more frequently when patients had insufficient knowledge of the organic event.

Real labyrinthine events did happen during the observed six to eight weeks. However, they were very seldom.

We may conclude, that patients with Meniere's disease usually suffer much less from labyrinthine vertigo attacks and more often and for a longer period of time from reactive psychogenic dizziness.

This phenomena can be sufficiently explained and treated by applying behavioral principles.

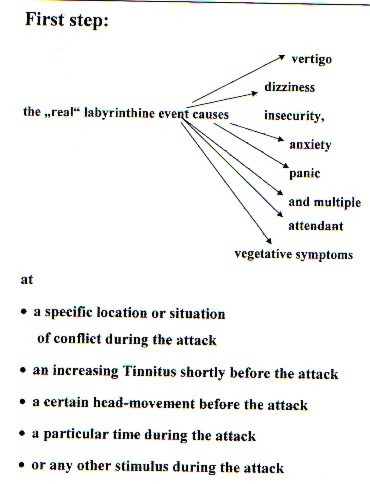

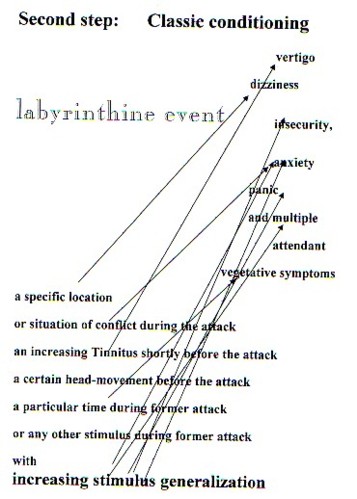

Pawlow's dog learned to respond to a bell as a food-stimulus.

During their labyrinthine vertigo attacks Meniere's disease patients "learn" to respond to other stimuli through mechanisms of classical conditioning. Frequently observed responses are: insecurity, anxiety, panic and multiple attendant vegetative symptoms .

These stimuli may be:

ñ the location of an attack

ñ a situation of conflict during an attack

ñ an increasing Tinnitus shortly before the attack

ñ a certain head-movement

ñ a particular time

Anxiety, as a reaction on vertigo attacks, may be experienced as a sensation of dizziness. This can easily lead to a viscous circle of anxiety-dizziness and dizziness-anxiety. We often observed psychogenic dizziness accompanied by clinically relevant symptoms of depression and anxiety.

It must be emphasized that these mechanisms operate subconsciously. So psychogenic dizziness can remain or establish itself even if the inner ear has already lost its function. This was true for four of our patients.

Interaction between Doctor and Patient

If the doctor is unable to visualise the possible progression of the illness,

then he is in danger of having to share his uncertainty with the patient.

Unfortunately, there is still a lot of unclarity surrounding crucial aspects of Morbus Meniere.

This led the Japaneses Ministry of Health to put Morbus Meniere on their list of 43 "difficult-to-treat" illnesses in 1974.

The origins of these illnesses are still unknown and the methods of treatment not yet secured.

Although this resulted in a research assignment of considerable size (11), there was still no success in finding curative methods or definite prognostic knowledge.

Furthermore, evident physical symptoms of vertigo can occur together with psychogenic forms, and it is often difficult to distinguish between the two.

Doctors can then feel unsure and also even confused.

Understandably, this can cause the therapist to react defensively and to have many different , often ambivalent feelings - such as protective impulses, helplessness and even aggressive impulses towards the patient - in an attempt to maintain his own stability - which is not necessarily in the interest of the patient!

At the same time the therapist comes under the pressure of the patient's expectation that something has to be done.

There is an underlying, unexpressed demand directed at the doctor, that he should give support and a sense of security, which the vertigo prevents the patient from having.

This pressure can become so great that the doctor then tries to do everything in his power to help, although there are no solutions or suitable medical facilities within his specialist medical field.

Attention is not always paid to the fact that a disappointment can also have serious side effects!

Also having an effect on the doctor, who knows that his conventional methods are not going to influence the root of the problem, is the patient's uncertainty and fear after the last attack and in anticipation of the next one.

This could also explain why a group of medicaments without proven effect such as the Betahistine, and groundless surgery such as the Saccotomie are used again and again.

Feeling backed up mainly by what we could call a "prop" ("for vertigo....our Betahistine") many practitioners are pleased to be able to hand out a medicament, which at least does not seem to have any damaging physical side effects, to their desperate patients. This is easy to understand, but not rational and also costly.(7)

A good neurootological counselling base

Other than in the time of Meniere and Luther, it is nowadays possible to sto the acute vertigo with Antiemetika.

If good counselling is offered, then some patients can be helped to prepare themselves prophylactically for unforseeable attacks.

Antiemetika in the form of suppositories can usually be effective just as quickly as it takes for the emergency doctor to arrive.

For patients, who are not prone to addiction, Tavor expidet as an sublingual quickly absorbed and strongly effective Diazepam to be taken as needed, can be prescribed.

This is counteractive, however, if patients, unaware of the difference or unable to distinguish between a state of anxiety and Morbus Meniere, take the medication at the first signs of dizziness.

It is therefore an important issue for the prescribing of medication and for the ensuing therapy process, that patients learn not only to distinguish between psychogenic and inner-ear vertigo, but also between psychogenic and other forms of vertigo (such as those caused by cardiac disorders and postional dizziness.

Patients can be instructed to choose a fixed point to focus on (such as the door frame) before the vertigo attack occurs.

They can then check whether everything spins around their ears - as is the case during inner-ear vertigo, or whether they can fix their gaze (19) on the chosen object - as is the case during psychogenic vertigo.

Another distinguishing criterion, which can be tried out independently during the fit of dizziness, is to stand up, to stamp firmly and to check whether steadiness can be achieved through this movement and whether the vertigo in the head diminishes.

This is a pragmatic way of counteracting the further unconscious development of the psychogenic vertigo.

With regard to the psychogenic component counselling itself can have the effect of reducing fear, when conditioning processes and the generalising effects of stimulus are explained. It would be unfavourable and demotivating to communicate verbally or non-verbally a demand such as "Pull yourself together!"

Established Therapies - Physical and Psychosomatic

If the physically caused vertigo is such, that quality of life and the ability to work are put into question, then it can usually be eliminated.

The price is high and can lead to the onset of loss of hearing.

The decision, for example, for a treatment with intratympanal gentamycin, which could mean endangering the function of the labyrinthine system or even disabling the inner ear, depends on many factors, which all have to be considered (2).

Consequently, one is more likely to recommend a "definitive" course of treatment to a patient with de facto deafness and frequent attacks of vertigo, than to a patient with severe attacks of vertigo but with good hearing ability, even if one shares the hope of Lange et al. (14) and believes that gentamycins should not harm the cochlear funktion, when applied "correctly".

With patients, whose ability to work has to be maintained, one is more likely to go for the sure solution, although it endangers the inner ear, than with patients, who are already in retirement and who believe that they can cope with their attacks.

Less easy - or not at all- able to be influenced, is the normal case of progressive loss of hearing.

Partial deafness in one ear can often be reduced enough for "daily use", but usually leads to loss of ability to hear directionally.

In this case, devices, such as hearing aids - adjusted to a low frequency (8) - , CROS hearing aids and even the cochlear implant for the unusual condition of deafness in both ears, can certainly bring improvement.

There is treatment for tinnitus, which is not experienced by the patients as being such a torment as the vertigo (12, 20).

There is therapy when anxiety and depression develope, just as there is for reactive, psychogenic vertigo.

Reliable psychotherapists should be consulted, who can count on the support of the ear, nose and throat specialist for the treatment of this medical condition (23).

Antidepressants can also be very effective (25), and should be prescribed by the medical psychotherapist or psychiatrist according to the individual situation. Except in the case of emergency, it is not advisable to prescribe sedatives and tranquillisers, because of their addictive qualities. As Paparella (17) in 1991 clearly expressed, reliable and confident support, as well as skill and good judgment, is necessary at all stages of Morbus Meniere.

In the meantime, drawing from 10 years of experience with mainly psychosomatic, clinical treatment, - and the above mentioned, - it seems that adopting an open and direct communicative approach towards patients with Morbus Meniere is better than a cautious "non-verbal" one.

Morbus Meniere is not a life-threatining diagnosis, but rather, in spite of everything, it is benign with mostly the loss of the functions of one ear; and it is not a disorder of the central nervous system, as a "stroke" is.

It is disadvantageous, and, thankfully, not justified to suspect the onset of Morbus Meniere (22, 28), when there is only cochlear endolymphatic fluctuation.

Otherwise, too many of these patients are in danger of developing a condition of psychogenic vertigo, through their fear and in anticipation of a Meniere attack.

It is advantageous, on the other hand, to encourage participation in self-help groups.

Help for the Ear Nose and Throat Doctor:

In order to feel confident, it is useful to have a basic knowledge of mental processes and to be able to reflect upon them. "Balint Groups", in which case-studies are focused on, and the own emotional involvement within the doctor-patient relationship is mirrored, can be helpful for doctors. Through gaining insight into psychosomatic processes in this way, it will then be easier for the doctor not to feel deliberately misled by the patient who cannot understand or act according to the - for the onlooker- plain and obvious facts.

Partial or further psychosomatic inpatient treatment can be of help when more support is required than can be provided for the outpatient. This can be especially relevant in the case of important psychogenic symptoms, and the development of depression and anxiety disorders.

Conclusions for the Doctor's Practice

The management of the patient with Meniere's disease remains a challenge.

Reliable care and attention has a positive effect within the treatment of this illness, with its recurring fits of vertigo, especially in the prophylactic treatment of the common reactive form of vertigo. The ears, nose and throat doctor is the first person the patient talks to who is in a position to make a definite judgment about the physical aspect of the illness. In addition to the E.N.T. findings, the personality structure, as well as the social and work situation of the patient, have to be taken into consideration, when therapy suggestions are made.

Literatur:

1. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutschsprachiger Audiologen und Neurootologen (ADANO) Leitlinie Tinnitus: http://www.hno.org/leitl.htm

2. Arnold, W. (2001) Die Qual der Wahl bei der Behandlung des Morbus Meniere. HNO 49 3 163-165

3. Eckhardt-Henn A; Breuer P; Thomalske C; Hoffmann SO; Hopf HC (2003) Anxiety disorders and other psychiatric subgroups in patients complaining of dizziness J Anxiety Disord; 17(4):369-88

4. Feldmann H, Lennarz H, Wedel, H von (1998) 2. Aufl. Tinnitus. Stuttgart, Thieme S. 28

5. Hallpike CS, Cairns H (1938) Observationes on the pathology of Meniere's Syndrom. Laryngo-Rhino-Otol; 53: 625-655

6. Hamann, K.-F (2002) Fahrtû¥chtigkeit bei vestibulûÊren LûÊsionen. HNO 50: 1086 - 1088

7. Hesse, G., Rienhoff, N. K. (1999) Medikamentenkosten bei Patienten mit chronischem Tinnitus. HNO 47: 658-660.

8. Hesse, G., Schaaf, H., Kolbe, U., Brehmer, D., Andres, R. (2000) Prescription of hearing aids for Meniere patients. In: Sterkers, O; Ferrary, E.; Daumann, R.; Sauvage, J.P.; Tran Ba Huy, R: (eds): Meniere's disease 1999 - update. Kugler Publications, The Hague. 681-683

9. Jahnke K (1994) Stadiengerechte Therapie der Meniereschen Krankheit. Dtsch Arztebl; 91: A 428-434.

10. James, Al; Burton M.J. (2001) Betahistine for MeniereÇs disease syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.; CD001873

11. Kitahara, M (ed) (1990) Meniere's disease. Heidelberg, Springer

12. Kolbe, U (2000) Analyse zu Kardinalsymptomen im Langzeitverlauf des Morbus Meniere. Vertigo, SchwerhûÑrigkeit, Tinnitus. Dissertationsschrift der UniversitûÊt Herdecke 2000

13. Kratzsch, V., Schaaf, H (2004) Fahrtauglichkeit bei Morbus Meniere. Die Problematik fû¥r Arzt und Patient. Tinnitus Forum 3- 2004. S. 46 - 60

14. Lange, G., Mann, W., Maurer, J (2004) Intratympanale Intervalltherapie des Morbus Meniere mit Gentamicin unter Erhalt der Cochleafunktion, HNO 52: S. 898-902

15. Meniere P (1861) MÕmoire sur les lÕsions de l'oreille interne donnant lieu Á des sympt¶mes de congestion cÕrÕbrale apoplectiforme. Gaz MÕd Paris 186, SÕr. 3, 16: 597-601.

16. Morgenstern, C: Morbus Meniere. In: Naumann HH (Hg) (1994) Oto-Rhino-Laryngologie in Klinik und Praxis, Bd. 1: Ohr. Stuttgart: Thieme; 768-775.

17. Paparella, MM (1991) Methods of diagnosis and treatment of MeniereÇs disease. In: Huang TS (ed.) Meniere's disease. Oto-Laryngol Suppl 485, Stockholm 108-119

18. Praetorius, Ch (1997) Krankheitserleben und BewûÊltigungsformen bei Morbus Meniere-Patienten. 2. Aufl. Neuthor Michelstadt S 121

19. Schaaf, H (2004) M. Meniere. Ein psychosomatisch orientierter Leitfaden. (4. Aufl.). Heidelberg: Springer; S. 222.

20. Schaaf, H, Holtmann H, Hesse G, Kolbe U, Brehmer D (1999) Der (reaktive) psychogene Schwindel - eine wichtige Teilkomponente bei wiederholten M. Meniere-AnfûÊllen. HNO; 47: 924-932.

21. Schaaf, H. Seling, B., Rienhoff, N.K. , Laubert, A., Nelting, M., Hesse G. (2001): Sind rezidivierende Tiefton - HûÑrverluste ohne Schwindel - die Vorstufe eines M. Meniere? HNO 49: S. 543 - 547 www.drhschaaf.de/HNOendo.htm

22. Schaaf, H., Hesse, G. Nelting, M (2002): Die Zusammenarbeit im TRT Team. MûÑglichkeiten und Gefahren. HNO (50) 572 -577

23. Schaaf, H., Holtmann, H. (2002) Psychotherapie bei Tinnitus. Stuttgart: Schattauer. S. 141

24. SchmûÊl, F., Stoll W (2003) MedikamentûÑse Schwindeltherapie. Laryngo - Rhino-Otol, 82 44-66

25. Seling, B (2005) Vorgehen und Behandlungsmassnahmen bei psychiatrischer Co-MorbiditûÊt. In Biesinger, E. (2005) HNO-Praxis heute, Band 25; Schwerpunktthema: "Tinnitus im ambulanten Bereich" - Im Druck

26. Thomsen J, Bretlau P, Tos M, Johnson NJ (1981) Placebo effect in the surgery of Meniere's disease - a double blind, placebo-controlled study on endolymphatic sac surgery. Arch Oto-laryngol 107: 271-277

27. Yamakawa, K (1938) û¥ber pathologische VerûÊnderungen bei einem Meniere Kranken. J Otolaryngl Soc Jap; 4: 2310-2312.

28. Yamasoba, T., Kikuchi, S., Sugaswa, M., Yagi, M., Harada, T (1994) Acute Low-Tone Sensoneurial hearing loss without vertigo. Ach Otololaryngol head Neck Surg 120 S. 532-535

to finish: I canÇt give any garanty for links oder links to other links,

1. 6 . 2005

Patient's Guidance with a clear diagnosis, but vertigo provoking perspective.

Dr. med. Helmut Schaaf

Dr. med. Helmut Schaaf